Trains play key roles in a number of Hitchcock films, including THE LADY VANISHES, SHADOW OF A DOUBT, and, of course, STRANGERS ON A TRAIN.

A train figures prominently in NORTH BY NORTHWEST. The train is the Twentieth Century Limited, which ran from New York to Chicago for 65 years.

Other forms of transportation (automobiles, planes) also play pivotal roles in NxNW—and, as if to point up the importance of transportation in the story, Hitch’s precocious cameo shows the director just missing his bus in Manhattan.

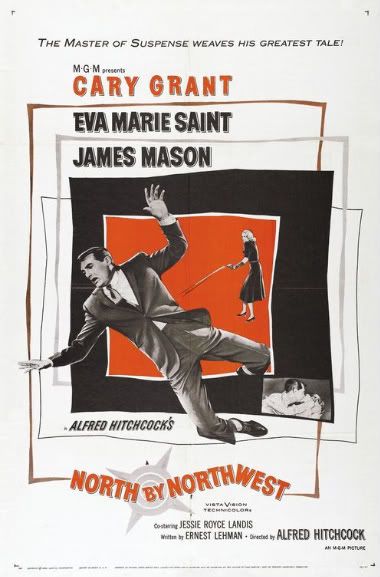

Famously, the plane in NxNW is a threat, as is the automobile. The bad guys use them creatively but ineffectively to try to kill the main character, Roger Thornhill, played with trademark suavity by Cary Grant, perhaps my favorite classic movie star, whose wit and elegance Hollywood has tried to rediscover in subsequent leading men from Tony Curtis to George Clooney.

But Grant is the quintessential leading man, in much the way that NxNW is the quintessential Hitchcock movie … by design, it turns out—screenwriter Ernest Lehman wrote the scrpt, he said, to be “the Hitchcock film to end all Hitchcock films.”

The modern world of machines is no friend of Thornhill—except perhaps for the train, even one ominously named after the century of American technology and global influence, which ambivalently both saves our protagonist and further complicates his already bad situation.

Like a number of Hitchcock’s other films, this one is an examination of American ethics and power—or the ethics of power—or, more particularly, it exploits Hitchcock’s delight in discovering menace in innocuous and seemingly innocent objects, people, and settings—smalltown America, birds, shy motel clerks, the Statue of Liberty, the U.N., sacks of potatoes, and the sunny wide-open spaces of the Corn Belt.

The trouble Thornhill finds himself in fairly early in the plot stems from the shadowy workings of a think tank in the U.S. Intelligence Agency, over which a man simply called The Professor, presides. The movie climaxes at Mt. Rushmore, where Thornhill tries to elude the bad guys one last time by scampering across the gargantuan, somewhat contemptuous stone faces of Presidents Lincoln, Jefferson, Washington, and Roosevelt, along with his newly found romantic interest, Eve Kendell (played by Eva Marie Saint in the archetypically glacial blonde mode Hitch favored in heroines).

So the film, planted firmly in the middle of the Cold War, is about espionage, not just as a plot device, but as a way to examine the absence of honesty in modern discourse, now that the USA is a world power.

NxNW has Hitchcock’s usual “wronged man accused of a crime he did not commit” in Thornhill, whose very name evokes Christlike suffering on a new Calvary. But Thornhill is no saint or innocent—his initials are “ROT”—and like the government bigshots who manipulate his reality, he, a Madison Avenue adman, manipulates the reality of the masses. Even more, he fakes chivalry to snatch other people’s taxicabs and escape crowded elevators, and he’s not above bribing his own mother to lie for him.

In the film, mirrored surfaces symbolize the characters’ duplicity and dishonesty—which Saul Bass’s opening credits set up, showing high-rise office windows in Manhattan, indifferently reflecting the comings and goings of the insignificant little citizens below.

The overall look of the film further stresses the point of how impersonal the world has become. Among other things, the movie is quintessentially a modernist work.

Many scenes seem deliberately allusive to Mondrian’s paintings—intersecting lines and sharp angles. The iconic crop-duster scene is carefully composed in diagonal and horizontal lines until, unexpectedly and suddenly, the plane flies directly towards the camera—and us the audience.

Hitchcock’s previous film VERTIGO focused on the fears and obsessions of James Stewart’s character and how they lead him to tragic realizations about his own dark motives, in part with the vibrant colors of San Francisco and the mesmerizing swirling of waves at Big Sur and Kim Novack’s hairdo. (The same swirling movement Hitch used again in PSYCHO, the shower water and blood whirling down the drain.)

Bernard Hermann’s musical score for VERTIGO is beautifully romantic, but his score for NxNW gallops with anxious intensity, punctuated at key moments with clashing cymbals.

NORTH BY NORTHWEST is, apart from Eve Kendell’s bright red coat at the end, almost devoid of color—with grays dominating virtually every scene—the Manhattan skyscrapers, the chrome train, and the looming stone faces at the end. Everything is oversize and threatening and, more importantly, inorganic—civilization removed from nature and humanity.

And deadpan incongruities like the housekeeper Anna’s farewell to arch-villain Vandamme with “God bless you” or the U.S. intelligence officer’s callous response to Thornhill’s life-threatening predicament (“It’s so horribly sad, how is it I feel like laughing?”) suggest to me that NxNW, which operates so obviously on the surface to be dismissible as “just entertainment,” embodies the director’s strongest critique of and skepticism about the dreams and values of his newly adopted homeland.

No comments:

Post a Comment