I used to rush home after elementary school to watch old Tarzan movies on a local TV station, every weekday afternoon at 4:00.

I was born in (north) Africa, so jungle pictures had a peculiar fascination for me because, by my logic, I was African. (I did technically hold dual citizenship till age 14, but my fancy attached itself solely to the romance of Africa, and not so much the Libyan Sahara, where I was born on a U.S. military base.)

My earliest erotic dream had me dangling from Tarzan’s bare feet as he swung from vine to phallic vine beyond a Mutia escarpment where I was Boy and Jane did not exist.

One Tarzan film in particular left its mark on me—a movie that, though heavily censored, retains a general air of rawness and menace, laced with Freudian sex-dream symbolism from beginning to end.

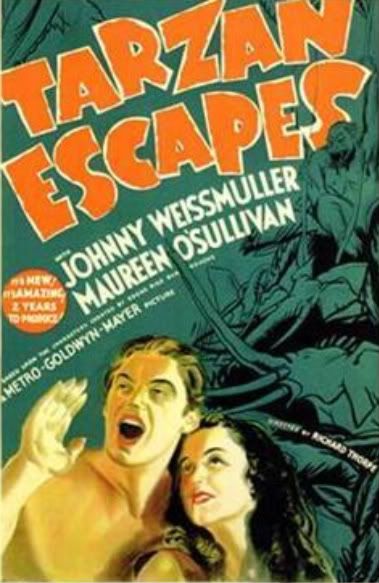

Of all the MGM Tarzan movies starring Johnny Weismuller, TARZAN ESCAPES, the third in the series, was the biggest problem for the studio. It went through two years of production and five directors—including William Wellman, who had directed the first Oscar-winning Best Picture (WINGS), and John Farrow, future husband of Maureen O’Sullivan (Jane) and, even later, Mia’s dad. Only Richard Thorpe is credited.

Adding to the movie’s mystique are rumors that the movie was jinxed. MGM producer Irving Thalberg died just as filming ended. John Buckler, who plays Captain Fry, died in a car accident a month before the premiere. Herbert Mundin, who plays Rawlins, died three years later, also in a car accident.

(As of this writing, the only surviving cast member is Cheeta the chimp, born in 1932 and holding the Guinness world record as the oldest living primate. He lives in Palm Springs—and paints for a living. His ghost-written autobiography—ME CHEETA: MY LIFE IN HOLLYWOOD—is scheduled for publication in February 2009.)

--Cheeta, Untitled Painting (2003)

Ruined by censors and “too many cooks in the kitchen,” the third in the Tarzan series is clearly inferior to the previous two. TARZAN ESCAPES was cut, re-shot, and re-cut before release, since the studio felt earlier cuts were too violent.

The first version, directed by James McKay, featured giant vampire bats attacking adventurers trekking through a swamp. The second version snipped out the bats and introduced a new character to inject some comic relief into what the studio chiefs felt had become an overly savage story.

The character of Rita, Jane’s cousin, was nastier in the original version and in the end was killed by a giant ape. Originally a crocodile killed the arch-villain Fry, who sinks with a subdued gasp into bubbly gunk in the released version.

Further diluting the movie’s brutal Darwinian implications, MGM built an elaborate tree house for Tarzan and Jane—full of Rube Goldberg devices that not only domesticated but gentrified the couple, with hot and cold water, a chimp-powered ceiling fan, and an elephant-powered elevator. The new split-level house helped to disguise the fact that the jungle couple was technically unmarried, a problem as the Motion Picture Code became stricter in the mid-1930s. (Three years later, when the couple was blessed with a “son,” the baby had to fall asexually from the sky—dropped by a plane, instead of a stork.)

Still, the third film retains vestiges of the sensationalistic first version.

What excited me most as a kid—and by “excited” I do mean “sexually excited”—was less Weismuller himself—athletic, 6’3”, but unusually pasty and depilated for a jungle lord—than the art direction. The overall “look” of the first three films oozes exotic, feral sexiness—not the least part of which was Tarzan’s skimpy loincloth.

The MGM jungle is all hairy vines, furled ferns, and soft-focus flowers—suggestive of virility and fecundity at once—a pansexual Eden. Everywhere we see erect, hulking, moss-covered tree trunks, even underwater, even in a cave! Lurking through the paradise, we have nature “red in tooth in claw”—lions, leopards, crocodiles, cannibals, even man-eating plants—a constant reminder that survival of the fittest is the only law this world understands.

As in the previous film (TARZAN AND HIS MATE—a tellingly crude word choice—even Frankenstein has a “bride”), swimming is a metaphor for sex. The nudity in the original Tarzan-and-Jane water ballet doomed the scene to Code censorship, so it is re-enacted, with clothes this time, in TARZAN ESCAPES. Tarzan coerces Jane to “swim,” but despite her squeals and protestations, Jane appreciates the fact that her man takes control.

Jane:

“Out here, Tarzan’s a king. How do I know what he’d be back there [in London]? Perhaps, at first, sort of a freak. And then, as he learned more about civilization, he’d realize he was dependent on his rich wife. He’d never tolerate that. Or if he did, it might be even worse.”

Fry:

“Oh, Miss Parker, this looks like your lord and master coming now.”

The early Tarzan films’ mix of sex and deadly force brings to mind Freud’s theory of eros and thanatos (sex drive and death wish) and hints at sado-masochistic fantasy—that is, the repeated “man-handling” of Jane suggests rape, while avoiding the reality. When Tarzan first encounters Rita, Jane’s cousin, he grips the hair on the back of her head—as if she were a kitten to be held by its scruff. Of course, Tarzan’s roughhousing is merely a primitive, masculine form of affection … or interest—but Jane knows that she and Tarzan have a form of love that the civilized world cannot understand.

This passion has to be sublimated in a Hollywood film, though. Midway through the movie, Tarzan wrestles a giant crocodile to its death and yodels his famous victory call. He hands Jane a water flower and stands over her. His shadow lurches over her reclined body, and with a slight shudder Jane lets the blossom slip from her fingers back into the river.

Bondage too is a key point of the plot—necessitating the eventual “escape.” The opening scene establishes Captain Fry as a captor of wild animals. His custom-designed duralium cages prevent the teeth and claws of untamed nature from ripping civilization to shreds—the latter embodied by Jane’s white-clad and well-coifed cousins, also introduced at the opening. Bars, booby traps, inhospitable terrain, and “juju” all work to segregate the savage from the civilized—but these are boundaries Jane and Tarzan are able to transcend.

Subsequent events prove that Fry is a villain (first revealed in his brutal treatment of black native workers), and Tarzan, of course, an embodiment of wild nature and Fry’s intended quarry, repeatedly proves himself to be, as one character puts it, a “gentleman.”

Ironically, if predictably, the hunters become the hunted. Natives capture Fry, the cousins, and Jane and tie them to tree trunks. In one of the most haunting images of execution suggested in film (but not directly shown), the natives tie two of the hunting party’s servants spread-eagle to slender trees, restrained by ropes and crisscrossed. When the ropes are cut, the trees spring apart, thus ripping the victims in half.

At the end of the movie Tarzan escapes from the cage Fry has locked him in and unties the adventurers, while his elephant friends stampede through the village. Tarzan and the hunting party escape the natives by slipping through a cavern (“juju” for the superstitious natives, who do not follow), and it opens amazingly to a swamp, which the cave links to mountains! The geography alone is a dream.

The cave’s features are unnervingly gothic. Darkness, mist, black bubbling pools, dead jagged trees. That it represents death is underscored by Jane’s line: “This is the first time in Africa I haven’t been able to see some sign of a bird!”

I believe the standard Freudian interpretation of dreamt caves with monsters inside is that they represent repressed fears of the self, particularly of the unruly id, fount of lust and rage. So the final obstacle Tarzan and his train face in this adventure story aptly symbolizes Production Code-era suppression of sex and violence in American movies.

When they reach the safety of the other side, Tarzan forces Captain Fry to return to the cave to his certain death. This act of primitive justice shocked and thrilled me as a boy, as it does even now.

And for me, as a kid, the fact that this cave squirms with iguanas (reptiles signify the id-driven penis in Freud), growling in the misty shadows, thrilled me all the more.

No comments:

Post a Comment