I don’t think any man of my generation did not see the 1963 Columbia Pictures production of Jason and the Argonauts in his boyhood. But behind the thrilling special effects supplied by Ray Harryhausen (a god to FX lovers and readers of Famous Monsters of Filmland), could there be a serious, maybe even subversive message?

It seems that a good portion of the film’s dialogue, written by Jan Read and Beverley Cross, concerns the belief in God or gods—about which little is said that is favorable to theism.

Having just watched the movie on DVD, I give you my notes:

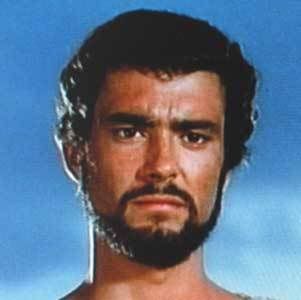

I. Hercules

When the giant statue Talos collapses on top of his young friend Hylas, Hercules complains that the gods are unjust. Talos comes to life because Hercules steals a Titan’s golden hairpin. Hylas in fact warns Hercules not to take the javelin-sized pin, so he’s entirely innocent.

Later, as Jason struggles to stop the vengeful statue, Hercules flees and drops his souvenir pin. Out of love for Hercules, Hylas runs back to retrieve it, but the falling giant crushes him.

Why should the gods punish an innocent boy for Hercules’ offense?

II. Phineas

Later, King Phineas makes another point about divine justice. Admitting that he has sinned and perhaps deserves Zeus’s punishments (harpies who steal the blind man’s food), Phineas states that he nevertheless does not sin every day, so why then must he be punished every day?

The question of perfect, proportionate justice is contradicted by continuous and everlasting punishment, for which even the worst sinners can not possibly pack enough offenses into their brief lives.

III. Jason

When the Argonauts are forced to pass through the Clashing Rocks, Jason accuses Zeus and the other Olympians of going “too far.” He complains bitterly, “The gods of Greece are cruel. In time all men will learn to live without them.”

Once Hera and Poseidon intervene to save the ship and crew, Jason offers only a well-qualified thanks. In a philosophical mood, Zeus decides not to punish Jason, stating that if he were to punish every blasphemy, no men would be left to worship the gods at all.

Hera remarks that once mankind stops believing in gods, Zeus will be “nothing.” Zeus agrees and notes that the fact that Hera stays by his side in the face of looming non-existence is almost “human.”

IV. Medea

Jason then rescues the princess Medea from the Clashing Rocks, when gods fail to intervene on her and her shipmates’ behalf. At the ends of the earth, where Jason and his men hope to find the legendary Golden Fleece, Medea, high priestess to the Underworld goddess Hecate, has a crisis of faith.

When her father the king arrests Jason for treachery and murder, Medea prays to the goddess to help her, even though she owes her life to Jason’s human intervention. She shares her dilemma with the statue of Hecate (whom, interestingly, the film never bothers to personify as anything but a stone icon). If Medea helps Jason escape, she is a traitor to her country and her gods, but if she does not, she is a traitor to herself.

Ultimately, at great risk, she helps Jason. But her father Aeetes in turn calls on Hecate for help. Through Hecate’s black magic, he raises an army of skeletons, the victims of the seven-headed hydra that Jason has slain to claim the fleece. Jason and his men fight the resurrected warriors by sword and hand to bony hand. Ultimately, Jason outwits the undead, and they fall into the sea.

* * *

The movie ends before the true end of the story (ultimately, Jason will spurn Medea, and in vengeance she will kill their children, along with the woman Jason hopes to replace her with).

The goddess Hera spares the movie audience this hopeless violence and provides a Hollywood ending, with Jason and Medea kissing.

However, despite the victory over the skeletal army of Hecate, two human adversaries remain for Jason—King Aeetes and King Pelias (who’s not seen after, in the film’s first 30 minutes, he tricks Jason to go on the quest so that Jason will not kill him for destroying Jason’s family and stealing the throne). (In the full myth, Medea disposes of both kings, in grisly ways worthy of Hannibal Lecter.)

Zeus and Hera agree to stop the chess game they’ve been playing with their human pawns … for the time being anyway. But clearly in their minds (and in the minds of the audience members familiar with mythology) the story (ultimately tragic) is far from over. The happy ending, then, is another ruse by the gods—whose shabby treatment of humanity has been repeatedly questioned throughout the film—but the movie audience is at least spared having to see the worst of it.

In the origional Greek mythology, the Gods where unjust bastards who cared more about their personal desires than things like justice, human life, or anything else of that matter. There are exceptions (Athena, hope of soldiers comes to mind- she is a partial exception), but for the most part the Gods of Greek mythology are NOTHING like the warm and fuzzy or viciously judgemental (your mileage may vary) God of monotheism.

ReplyDeleteYou are reading to much into it- they probably were working of the source material. Remember, Prometheus was sentanced to eternal torture because he disobeyed Zeus and helped humanity. Oh and he had helped Zeus kill his father so he and his siblings could live because Zeus's father, Kronos had eaten them. The Greek Gods were complete and utter bastards.